Welcome to Day 6 of ‘8 Days – 8 Reasons to Repeal the 8th’, where each day running to International Women’s Day, Abortion Rights Campaign will be busting 1 common myth about abortion in Ireland.

So check back here for tomorrow’s myth and tweet your own at us @freesafelegal and using #RepealThe8th.

Today, in partnership with AIMS Ireland, we bring you:

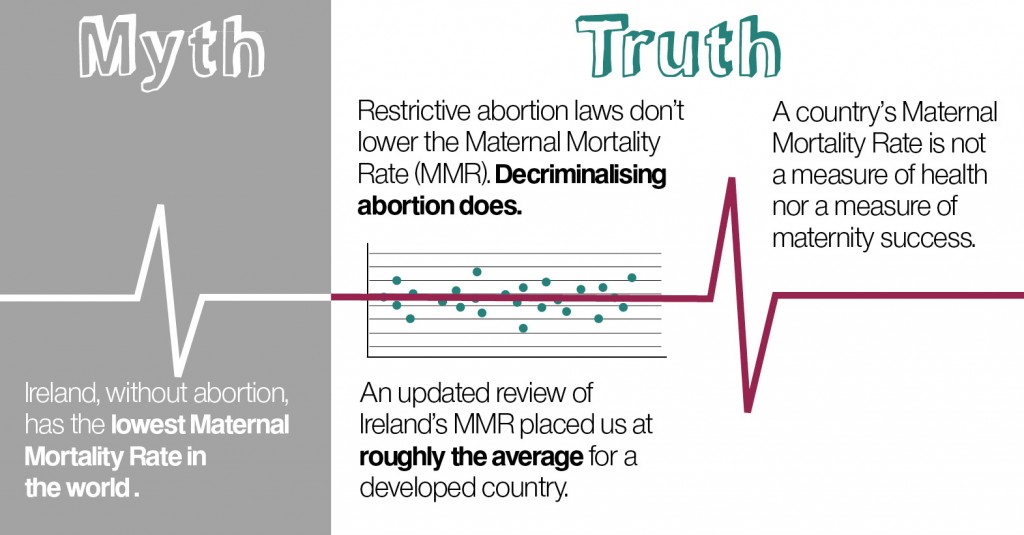

Myth #6: Ireland, without abortion, has the lowest maternal mortality rate in the world / Ireland, without abortion, is the safest place in the world for pregnant women.

But the truth is much simpler:

Truth #6: Ireland’s Maternal Mortality Rate is roughly average for a developed country. In fact, many countries providing women with access to safe and legal abortion report below-average MMRs.

The mother of all anti-choice myths during debate surrounding last year’s abortion legislation. Even if it were true (it’s not), it would still be irrelevant.

A combination of cherry-picked statistics and the presupposition of a nonexistent correlation between restrictive abortion laws and lower maternal mortality rates makes up the foundation of this non-argument. The proverbial cherry comes courtesy of Maternal Mortality in 2005, a World Health Organization (WHO) report that gathered statistics on MMRs globally in that year. Ireland’s was a conspicuously implausible one per 100,000 live births. Or was it?

The authors of the study prefaced their findings with three significant caveats concerning the data collection process, which are worth quoting at length:

[I]t is difficult to measure accurately the levels of maternal mortality in a population – for several reasons. First, it is challenging to identify maternal deaths precisely – particularly in settings where routine recording of deaths is not complete within civil registration systems, and the death of a woman of reproductive age might not be recorded. Second, even if such a death were recorded, the woman’s pregnancy status may not have been known and the death would therefore not have been reported as a maternal death even if the woman had been pregnant. Third, in most developing-country settings where medical certification of cause of death does not exist, accurate attribution of female deaths as maternal death is difficult. Even in developed countries where routine registration of deaths is in place, maternal deaths may be underreported, and identification of the true numbers of maternal deaths may require additional special investigations into the causes of deaths.

The honesty and restraint shown by the authors in these concessions is unfortunately lacking in those who judiciously extract from the report only the information favourable to their own ideological bias. The phenomenon of under-reported MMRs in developed countries has further been widely documented over the past two decades in medical journals in Ireland and internationally. All three difficulties raised above go some way towards explaining the supposed peerlessness of Ireland’s MMR as reported in 2005: it was determined with reference to crude Central Statistics Office data alone.

In 2009, four years after the publication of the WHO study, Maternal Death Enquiry Ireland (MDE Ireland) was established. It set out more thorough processes and criteria for gathering and analysing maternal mortality data, bringing Ireland at last into line with accepted best practice internationally. MDE Ireland’s report for the years 2009–11 rectified Ireland’s under-reporting and showed the national MMR to be in fact roughly average (eight per 100,000 maternities) for a developed country.

Now, even if Ireland were the world leader in maternal care, the suggestion by anti-choice voices that legislative restrictions on abortion contribute to lower MMRs would still be thoroughly baseless. Many countries with comparatively liberal abortion laws report below-average MMRs, even taking into account under-reporting. The MMRs of Norway and Sweden, for example, where abortion is effectively available ‘on demand’, are both slightly lower than Ireland’s.

What’s more, the MMR of a developed country is usually a single-digit figure or very low double-digit figure per 100,000 maternities. The incidence of maternal death in the developed world is so rare and subject to so many variables and external factors as to render comparison with a view to crowning a leader in maternal care based on MMRs alone meaningless.

Conversely, in many less-developed countries where termination of pregnancy is illegal and access to safe, legal abortion services in neighbouring jurisdictions is unavailable, unsafe (‘backstreet’) abortions do raise MMRs. In such countries the provision of safe, legal abortion services by trained professionals in medically appropriate environments would contribute to a reduction in MMRs towards the developed-world average.

It may take a rummaging through the relevant medical literature and a more thorough reading of the small print before this myth’s shoddy architecture gives way. But when it does give way it falls to pieces.

Of course, MMRs have nothing to do with whether or not women are happy or healthy, and it goes without saying that we should aim higher than merely stopping women dying. Women need full reproductive rights, including access to safe, legal abortion, and good-quality maternity care.